Three Americans in Paris, Pt. I

Today: a Lacanian psychoanalyst and the woman that had Hemingway listening

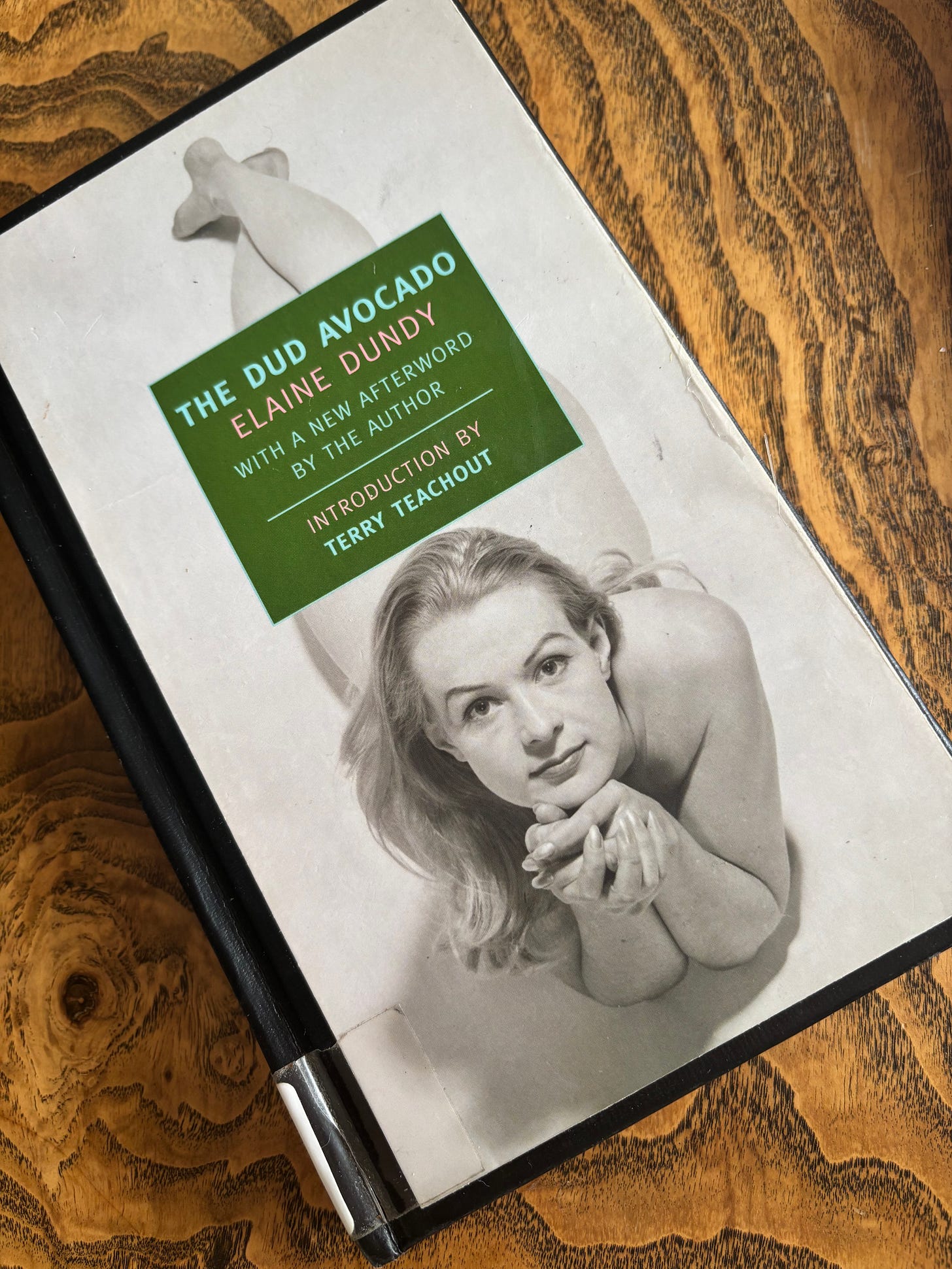

Within the first few pages of the 1968 American-in-Paris cult classic The Dud Avocado, we’re treated to a monologue on tourists in the City of Love from Larry Keefer, the lifelong crush of our protagonist, Sally Jay Gorce. Over lunch, Keefer asserts:

The tourist can be divided into two categories: the Organized [and] the Disorganized.

Under the Organized you find two distinct types:

the Eager-Beaver-Culture Vulture with the list ten yards long, all to be crossed off before she collapses of aesthetic indigestion;

and second, the cool suave Sophisticate who comes gliding over gracefully, calmly, and indifferently, but don’t be fooled. She’s determined to maintain her incorruptible standards of cleanliness and efficiency if her entire hotel staff dies trying…

The Disorganized, they get split into two groups as well.

First of all the Sly One. The idea is to see Europe casually, out of the corner of the eye. Museum catalogues immediately discarded as too boring and too corny. The general ‘feel’ of the country is what she’s after…but scratch the Sly One and out comes the real fanatic…secret pamphlet readings, stained-glass studying, wild aesthetic discussions of the relative values of the two towers at Chartres.

The last type is the Wild Cat. The I-am-a-fugitive-from the Convent of the Sacred Heart. It’s her first time free and her first time across…something snaps in the American girl and she’s off.

The story that follows is one of a Wild Cat, or, as Sally Jay reluctantly self-identifies, “tourist, second-year, disorganized.”

The Dud Avocado is set in the 1950s, and its protagonist, Sally Jay Gorce, feels like a wittier, freer precursor to our current American envoy abroad, Emily in Paris. Sally Jay and Emily do share similarities (“an inability to dress appropriately” being one of Sally Jay’s self-declared flaws), but the difference is: Sally Jay slinks about Paris, attempting, and typically failing, to get it right; whereas Emily forces her American pluckiness upon a city that neither wants nor needs it.

In The Dud Avocado, Paris serves as the glittering backdrop for a series of Gorce’s youthful blunders. Most of those stumbles are into relationships with the wrong men, but the book is never heavy; not when she finds herself with a vindictive Italian, a dull Canadian tortured by his own good looks, or even an American criminal.

Gorce is never really behaving well, but she’s charming for her ability to admit that she knows doing the wrong thing, and just can’t help herself. There’s not a hint of perfectionism or self-consciousness to her character; she’s a real and a refreshing break from the heroines we’ve come to expect, who often exist as one of two binaries: perfectly polished or incurable mess.

The story is loosely based on the year author Elaine Dundy spent in Paris “escaping [her] family and wanting to be discovered” in her youth. What happens in The Dud Avocado loosely mirrors Dundy’s own experience, but, in her words: “all the impulsive, outrageous things my heroine does, I did. All the sensible things she did, I made up.”

The book got a serious American-in-Paris stamp of approval, when Ernest Hemingway wrote Dundy:

“I liked your book. I like the way all the characters speak differently. My characters all sound the same because I don’t listen.”

That was hardly her only accolade: there were letters from Groucho Marx, a request to run away together from Laurence Olivier, and rave in the Financial Times. Her husband, the successful theater critic Ken Tynan, who had encouraged her to write in the first place ,was incensed at her success. He threatened to divorce her if she wrote another book, as he’d married an “actress, not a writer.” Of the incident, Dundy said:

“Ken said to me ‘if you write another book, I’ll divorce you.’ I sat down and started my second novel.”

Sally Jay would approve, bien sûr.

A quick guide to living like Sally Jay:

Wear an evening dress at midday (“dress it down” with a red leather belt, as she does in the book’s opening scene)

Attain French fluency and a charming enough accent to extricate yourself from sticky situations with the police (as the book’s author, Elaine Dundy, had to do)

Become a star of the stage, dedicating your days to rehearsals and your evenings to captivating audiences

Go on a road trip with a group of people you barely know, complain the entire time

Restrict your drinking: only Pernod Pastis or champagne (when drinking at the Ritz on someone else’s tab) will do

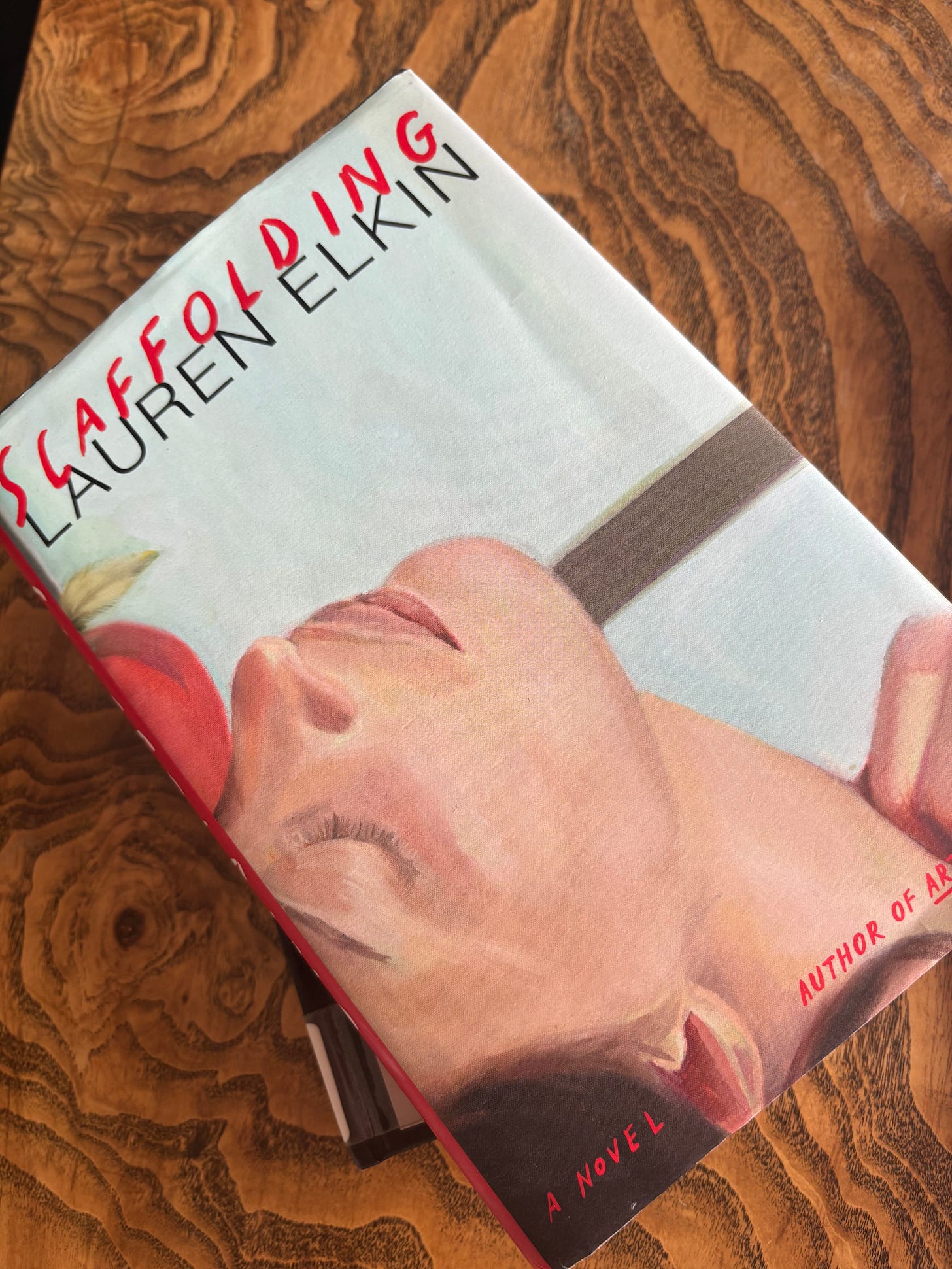

I didn’t deliberately select a Parisian pattern for my winter reads, but the moment I dropped The Dud Avocado, I procured Lauren Elkin’s Scaffolding, a book I read about ages ago in

’ newsletter, and have wanted to read since. When I saw it on a featured table One Grand Books, I knew it was time to dive in.Here’s where I admit that “three Americans in Paris” is a misleading-ish title1. Scaffolding’s protagonist, Anna, is French, born and raised. Her father is American, though, and her French cousins mock the American habits she’s picked up from trips across the pond, so let’s allow it.

Grouping these two books together isn’t me telling you they’re for the same type: they’re not. Scaffolding is far heavier, and perhaps a bit less fun to fly through (though I couldn’t put it down), but nonetheless a beautifully-written pleasure to read.

When I began publishing book reviews online in 2015, one day, sick of reviewing the same things everyone else was, I plucked a random book off the Barnes & Noble shelf: it was called The 6:41 to Paris. I fell in love with its French frankness, and began seeking out French novels in translation, reviewing The Case of Lisandra P, Based on a True Story, The Yellow Eyes of Crocodiles and The Perfect Nanny in rapid succession.

The French refer to small talk as: “parler de la pluie et du beau temps,” which roughly translates to: talking about the rain and nice weather. In the words of an actual French person: “small talk is not a French habit because we are educated to just shut up when we have nothing to talk about.”

Though Elkin herself isn’t French, she has an MPhil from the Sorbonne, lived in Paris for twenty years, and has professionally translated Simone de Beauvoir’s work into English. Her work feels French in that it follows that incisive pattern of those other Gallic novelists I’ve read and loved. No inane patter, lots of back and forth and debates on the human condition. And the depth never feels forced or stilted; the conversational rhythms feel true to the characters, occasionally foreign, but always fascinating, to my small talk-trained American ear.

Scaffolding is a story of three women and one building. We meet our protagonist, Anna, in 2019. A Lacanian psychoanalyst by trade, she lives in an apartment in Paris’ predominantly Jewish suburb of Belleville with her husband David. In the wake of a devastating late-stage miscarriage, she’s been on leave from work and is almost permanently apartment-bound, save for daily trips to the bakery and the occasional run.

During this period of convalescence, one of the building’s new residents, Clémentine, a 24-year-old university student, stops by to introduce herself. Anna quickly becomes fascinated with Clém and her young, hungry brand of feminism; she’s a grad student by day and a member of a guerrilla group that pastes up signs about femicide around Paris by night.

Anna and Clémentine’s friendship exists, for months, in the confines of Anna’s home. Until one night, Clémentine finally convinces her to come out to a party, where she’s confronted by a figure that looms large over her past, and she finally begins to grasp the concept of unshakable, historical trauma.

In the midst of Anna and Clémentine’s story, there’s an interlude. We stay in their building, but we rewind back to 1972, and come face-to-page with the tenants that inhabited Anna’s apartment during that decade. They’ve inherited the Belleville home from Henry’s grandparents, a Polish Jewish family that miraculously skirted death and the destruction of their home during the war due to a clerical error on the Nazi deportation list.

Henry is content with his simple life as a paralegal, but Florence, in graduate school for psychoanalysis, wants more, including a baby, something she and Henry hadn’t discussed before marriage. Incensed by Henry’s refusal, Florence seeks solace in the form a torrid affair with her brilliant professor Max, a student of Lacan. When Henry discovers the affair, his reaction repulses Florence, and she begins to realize the fundamental chasm in the ways they view the world.

The three women’s lives connect in ways both obvious and unexpected. They reckon with fidelity, trauma, and feminism across the decades. They struggle to contain their more reckless longings, and they are suffocated by the roles they occupy as women in the world, though each woman wears the discomfort in a different way. I didn’t relate to a single character (perhaps where my puritanical American streak jumps out), but I loved discovering the ways they related to the world.

After hundreds of pages that feel like a fever dream, the book comes to an abrupt, tidy end. At first I was frustrated, then I understood that it was intentional, a mimicry of the pace of life. Certain moments, problems, and months stretch out long enough to feel like decades, and then, before you’ve even realized whatever once occupied your every waking hour no longer does, life has moved back to its normal rhythms. And then the cycle begins again.

At first blush, Scaffolding and The Dud Avocado don’t share much in common apart from their Hausmannian backdrops, but they’re both about women figuring out their place in the world, with frequent stumbles along the way.

Speaking of which, our third American in Paris is slightly tardy and couldn’t make it to this week’s newsletter party…but we’ll be back next week or the following to explore the mark she made on the City of Light (hint: you probably already know of her, but there’s definitely a lot about which you had no idea).

À bientot!

Even more misleading now than when I first drafted this, because we won’t be meeting our third American until next week or the week after. “One American in Paris, another who is French but has an American dad, and one who I’m actually not writing about until next week” didn’t quite have the same ring to it. Alors, c’est la vie!

👏👏👏